No and Low-Alcohol Wine: Demand, Production, and Future Trajectory

- Introduction

- From YOLO to NOLO

- Demand: declining consumption and health motivations

- Supply: quality improvements and production economics

- Summary of drivers

- Reduce and reuse to make NOLO

- Thermal distillation approaches

- Membrane-based approaches

- Comparative summary

- NOLO has ample room to grow

- Headwinds

- Mitigation options

- Positioning and outlook

- References

- Appendix 2 - Definition of no and low alcohol wine (NOLO)

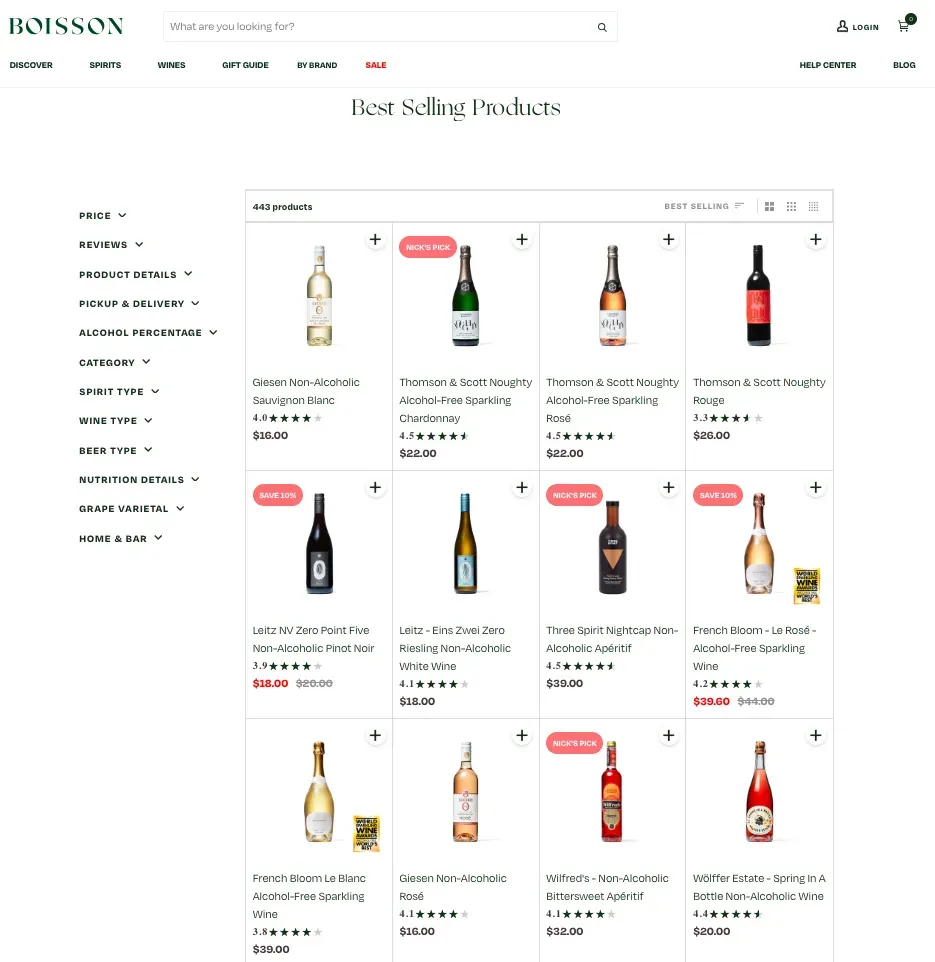

- Appendix 3 - Best selling products on Boisson are priced higher than traditional wine

“This essay was originally written as part of a professional wine examination. It has been lightly edited for clarity and web reading.”

Introduction

This opening section frames the scale of recent interest in no- and low-alcohol wine (NOLO) and previews the market and production questions examined in the essay.

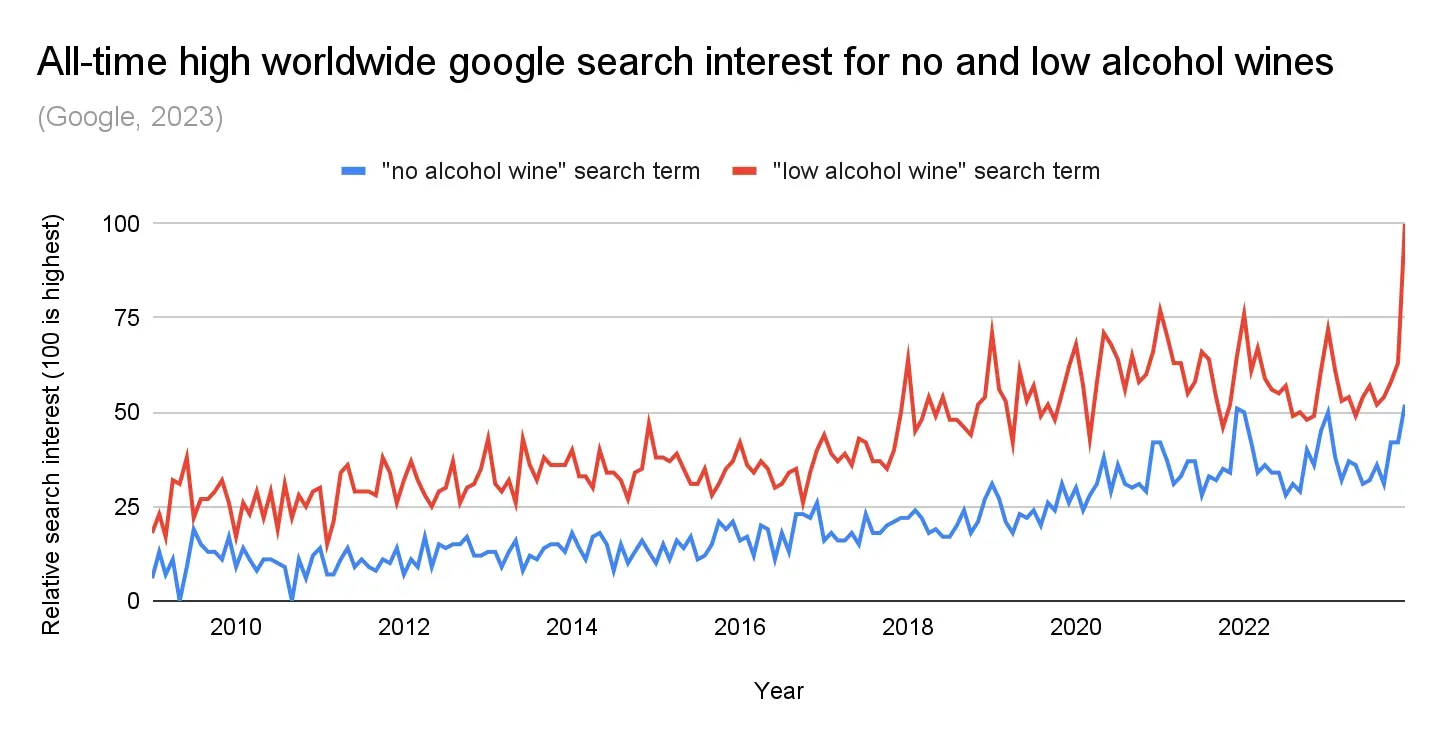

Interest in no and low alcohol wines (NOLO) has never been higher. This <11% alcohol by volume (ABV) category[^1] just hit a new peak in worldwide Google searches (Google, 2023); it is also the trending topic at major wine exhibitions (Carter, 2023).

Figure: Google Trends interest in no and low alcohol wine.

Figure: Google Trends interest in no and low alcohol wine.

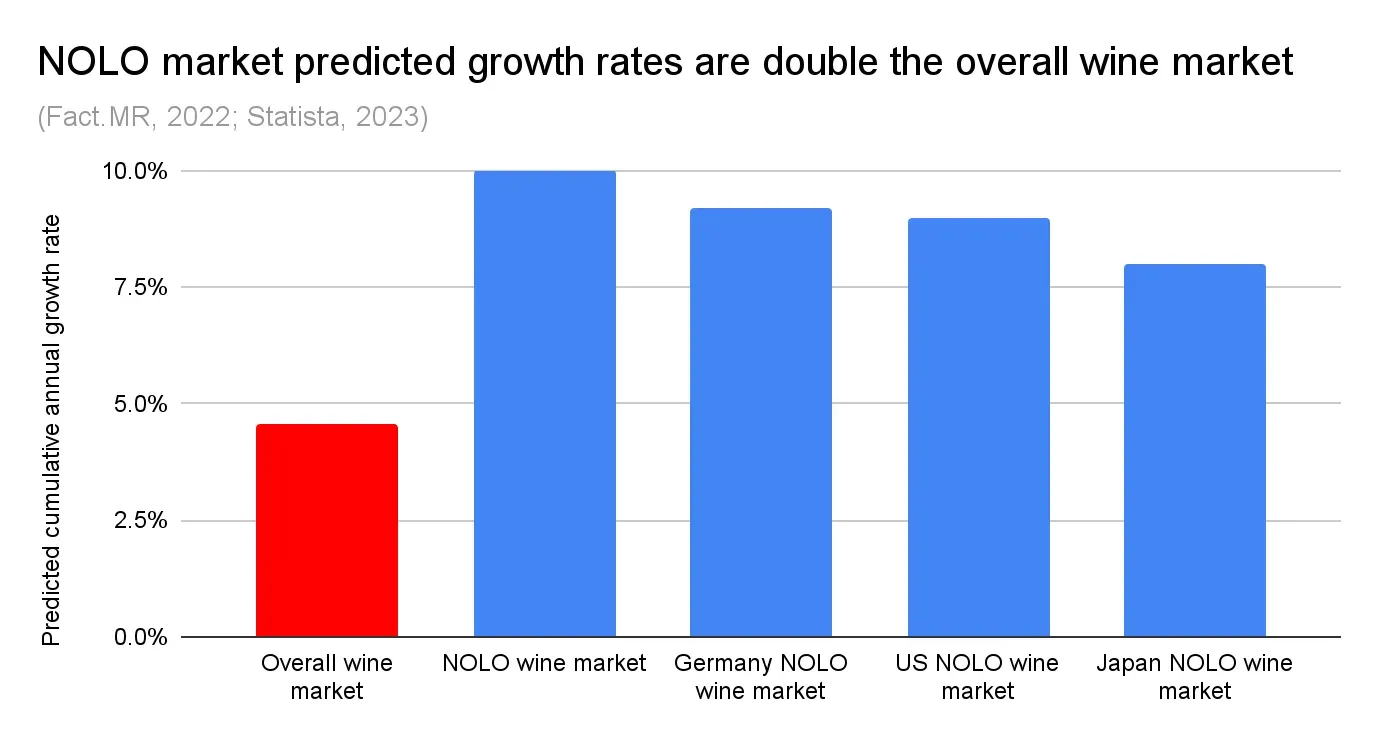

With worldwide NOLO sales predicted to grow twice as fast as the overall wine market, and this rapid growth expected across major wine consuming countries, the race is on to secure first-mover advantage in a category still in the introduction stage of its product life cycle (Fact.MR, 2022; Statista, 2023). High volume producers (e.g. Yellow Tail) and low volume wineries (e.g. Barton Guestier) alike are experimenting with NOLO as a new revenue stream (Frank, 2022).

Figure: Projected NOLO market growth relative to the overall wine market.

Figure: Projected NOLO market growth relative to the overall wine market.

The paper is structured around three questions:

-

Why NOLO is growing fast, from a demand and supply perspective

-

How NOLO is made, with resulting tradeoffs in quality and price

-

Where NOLO can go, and my contrarian opinion on NOLO marketing

From YOLO to NOLO

This section examines the demand- and supply-side forces behind NOLO’s growth, tracing shifts in consumption, health perceptions, and production capability.

Demand: declining consumption and health motivations

NOLO’s growth can be attributed to (1) Decreased alcohol consumption due to social and political factors, impacting demand (2) Improved NOLO product quality driven by economic and technological factors, influencing supply. The increased demand for NOLO attracts new supply, in a reinforcing growth loop that has excited both consumers and producers.

Alcohol consumption has declined in recent decades, particularly among the younger generation (Loy et al., 2021). This shift has led some consumers to substitute traditional alcoholic wines with NOLO alternatives, as outlined in a World Health Organization (WHO) report (World Health Organization, 2023). For example, “Dry January” started as a discussion about having a temporary break from drinking[^2] (Alcohol Change UK, 2023).

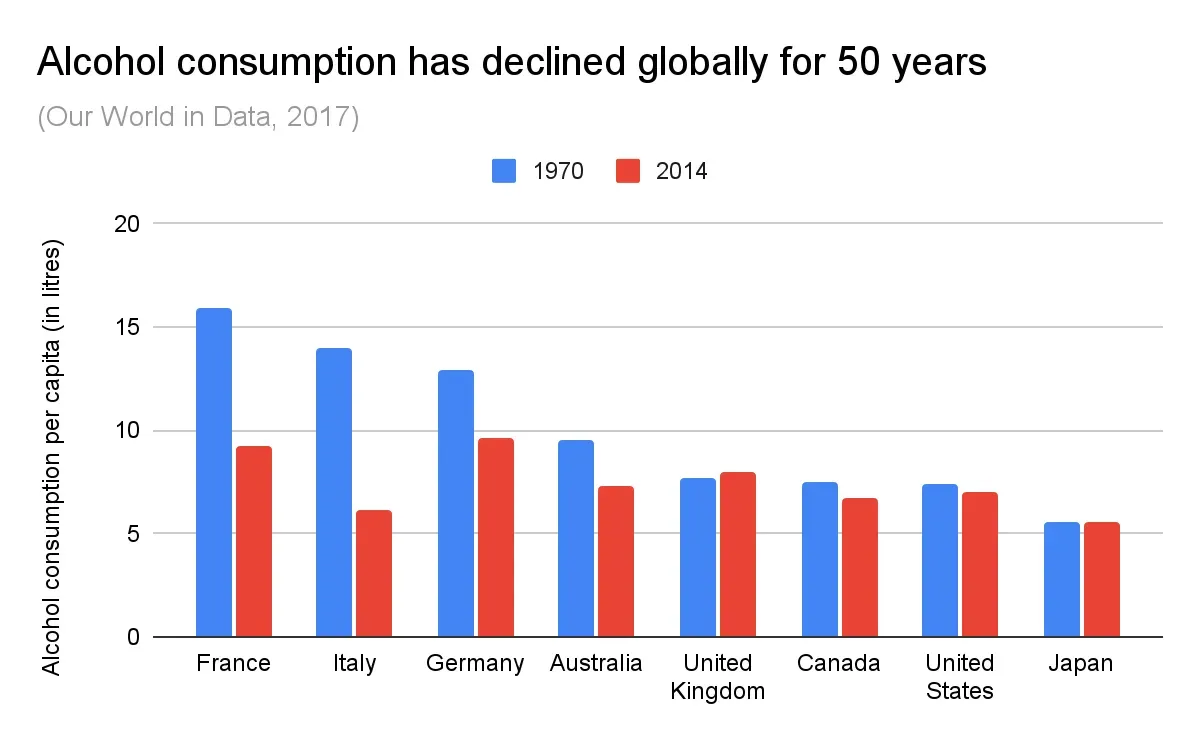

Research indicates that the decline in alcohol consumption has been a global phenomenon for the past 50 years, and not country specific[^3] (Our World in Data, 2017).

Figure: Long-run decline in alcohol consumption across countries.

Figure: Long-run decline in alcohol consumption across countries.

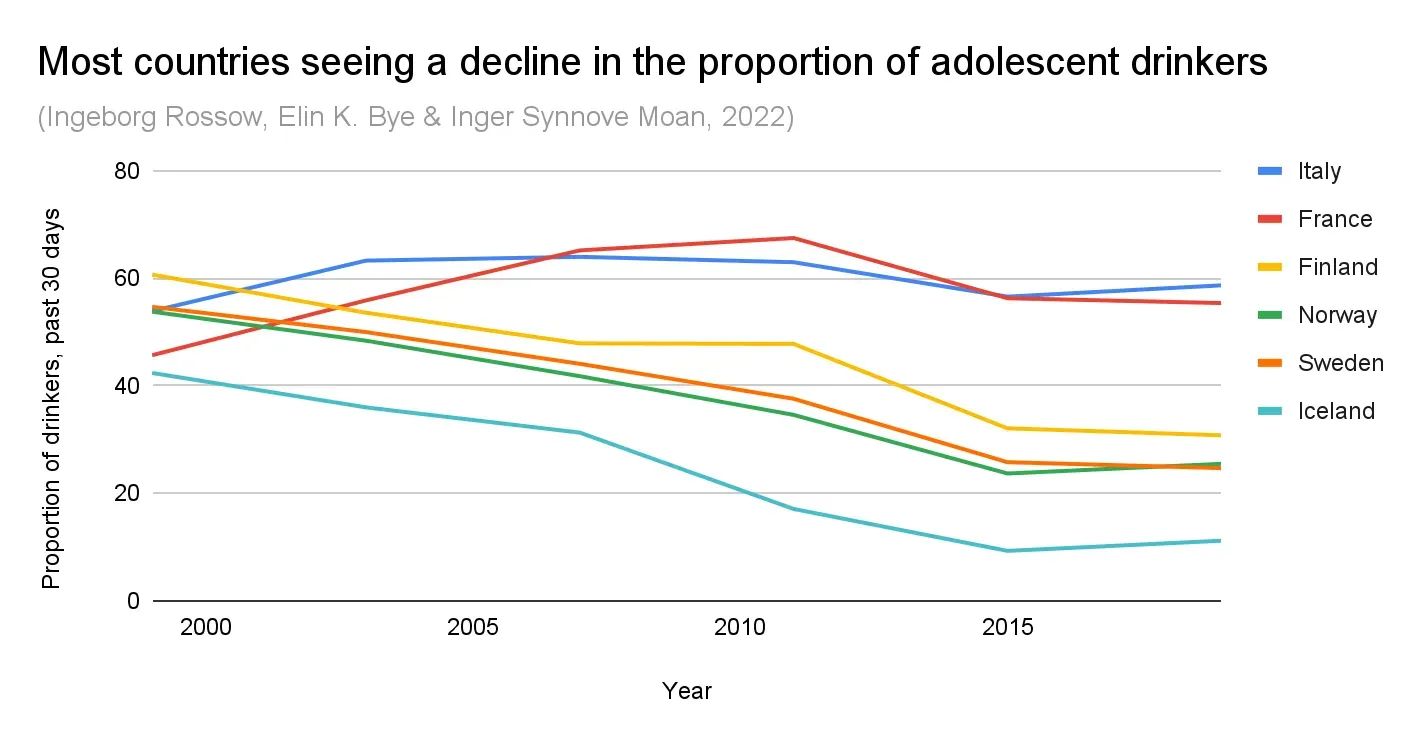

A 2022 study of Nordic and Mediterranean countries also showed mostly declines in the proportion of adolescent drinkers (Rossow et al., 2022).

Figure: Adolescent drinking declines in Nordic and Mediterranean countries.

Figure: Adolescent drinking declines in Nordic and Mediterranean countries.

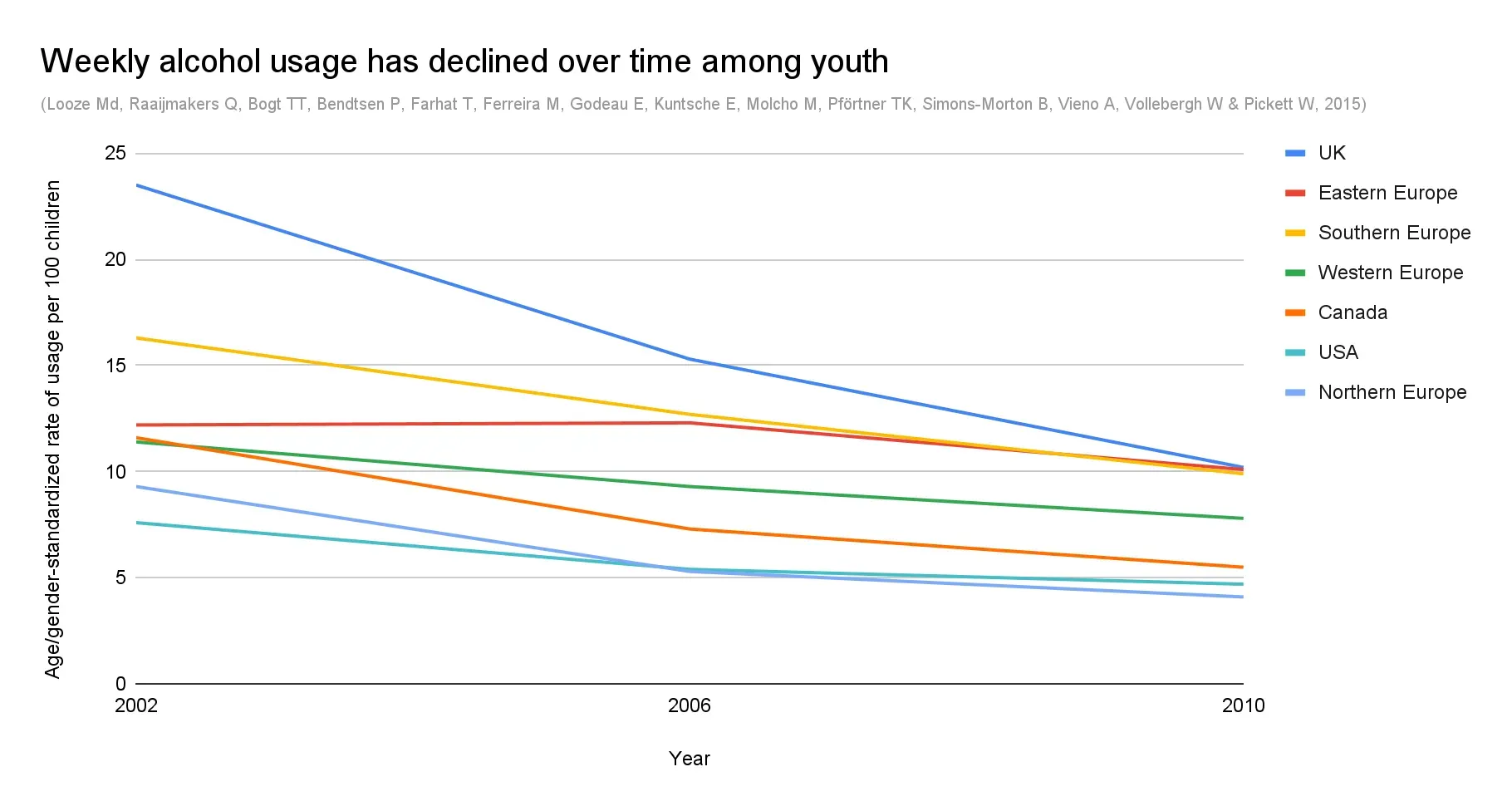

A more extensive study in 2015 concurred, revealing a gradual decline in alcohol use among both European and North American youth (Looze et al., 2015).

Figure: Youth alcohol use declines in Europe and North America.

Figure: Youth alcohol use declines in Europe and North America.

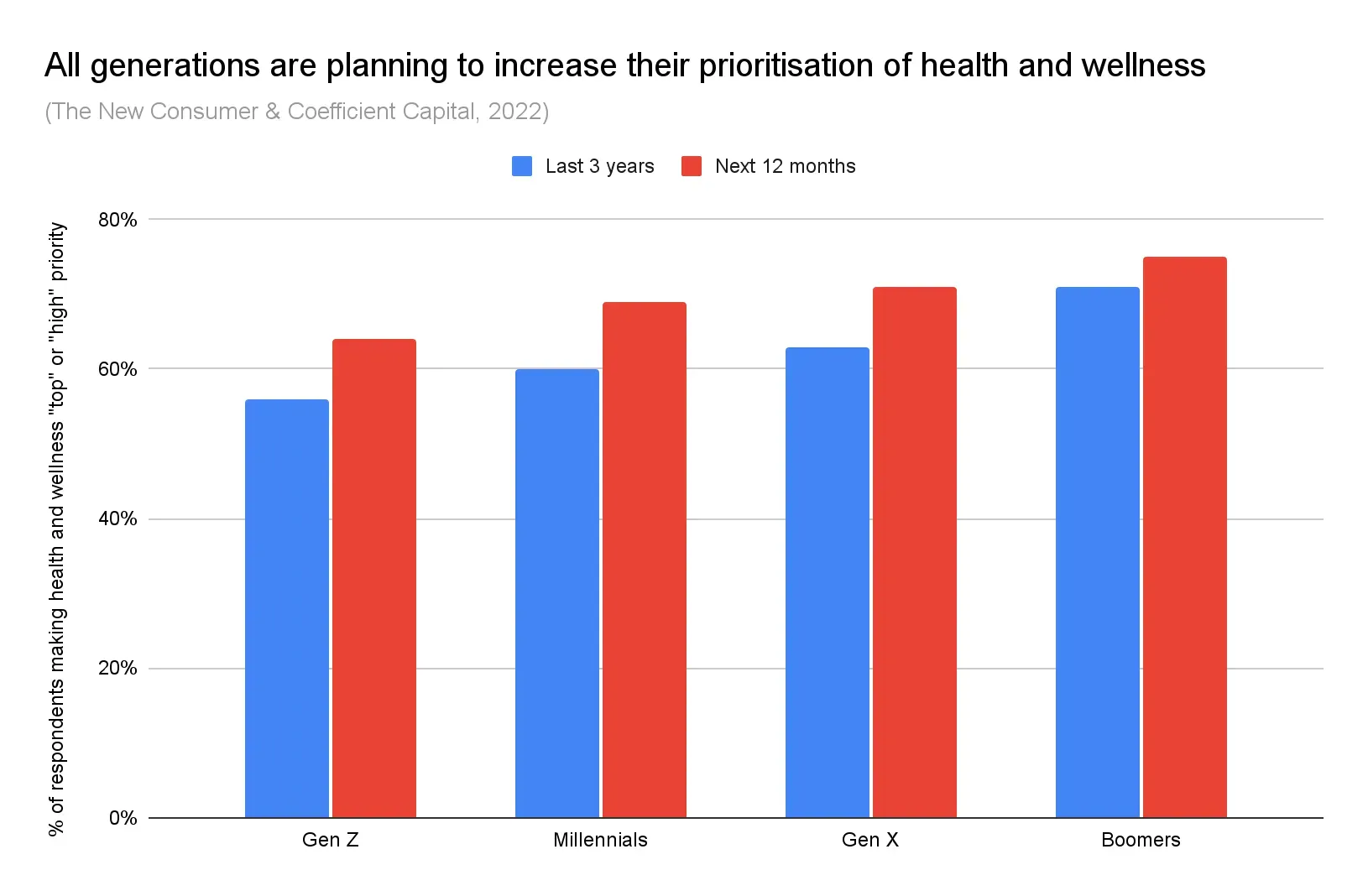

Health is the main reason for this decline. In a turnaround from the “You Only Live Once (YOLO)” mentality of the past[^4], people today are increasingly health conscious. Consumers are still worried about not fully experiencing life, but are also concerned that their health might prevent them from doing so, and changing what they consume as a result (Texas Health, 2023). Across generations, people are increasing their prioritisation of health (The New Consumer & Coefficient Capital, 2022).

Figure: Surveyed shifts toward health prioritization.

Figure: Surveyed shifts toward health prioritization.

For example, ~35% of American consumers surveyed adopted new eating patterns to “prevent future health conditions” (International Food Information Council Foundation, 2018). The 2020 COVID pandemic also put a spotlight on this social norm, with consumers being more observant of their health as a result (NutriSystem, 2023).

Beyond the social aspect, politics have played a role in shaping attitudes toward alcohol, by increasing awareness of its adverse health effects. With the World Cancer Research Fund finding strong evidence that alcohol consumption increases cancer risk[^5], and the WHO estimating harmful alcohol usage represents 5% of the global disease burden[^6], governing bodies such as the EU are considering stronger alcohol regulations (World Cancer Research Fund, 2018; World Health Organization, 2022).

These regulations are typically aimed at restricting and reducing alcohol consumption (Looze et al., 2015; Goold et al., 2017). The stronger the national alcohol policy, the lower the alcohol consumption in that country (Brand et al., 2007). For example, over a period of 50 years Norwegians have reversed their attitude and become increasingly supportive of alcohol control policies, due to increased awareness of alcohol health risks (Rossow & Storvoll, 2013).

Because of these social and political factors, consumers are reconsidering their relationship with wine, believing that reducing alcohol consumption will decrease calorie intake, blood pressure, and cancer risk (World Health Organization, 2023). Additionally, for women, considerations related to pregnancy and nursing have driven them to explore NOLO, as noted by Dawn Maire, founder of a NOLO startup (Reiley et al., 2023).

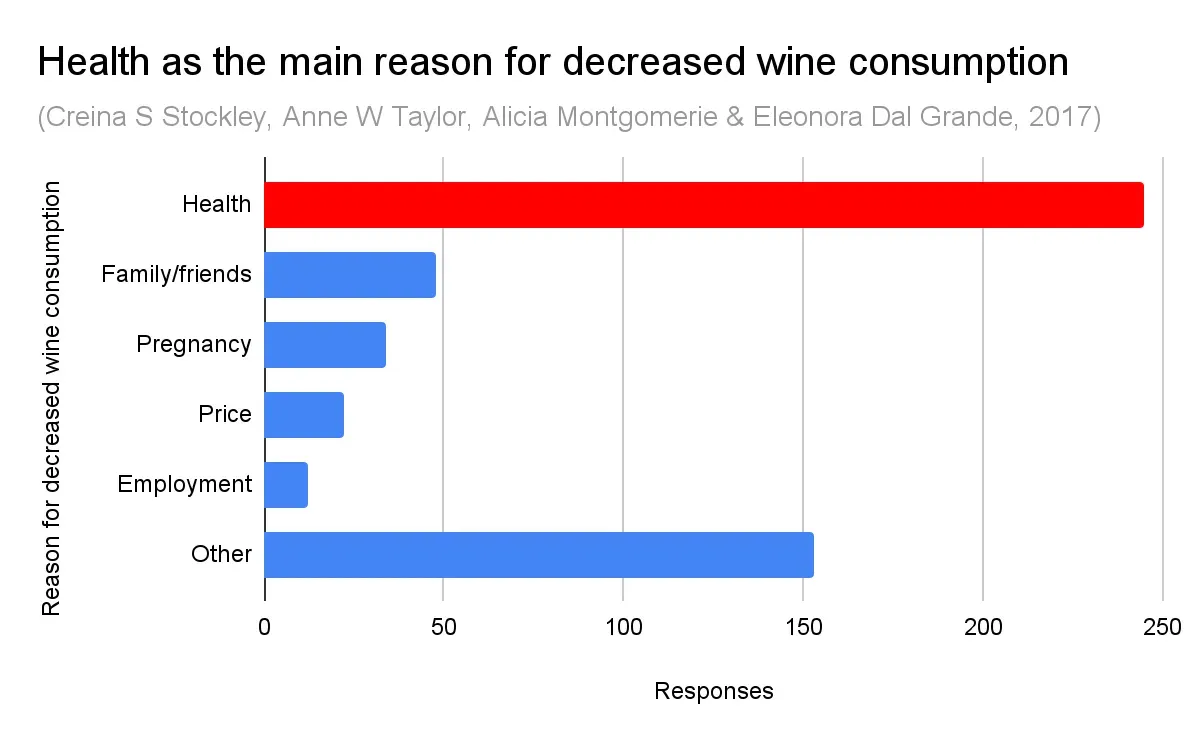

For example, a 2017 study found that “health” was the main reason participants decreased their wine consumption[^7] (Stockley et al., 2017).

Figure: Health as a primary reason for reduced wine consumption.

Figure: Health as a primary reason for reduced wine consumption.

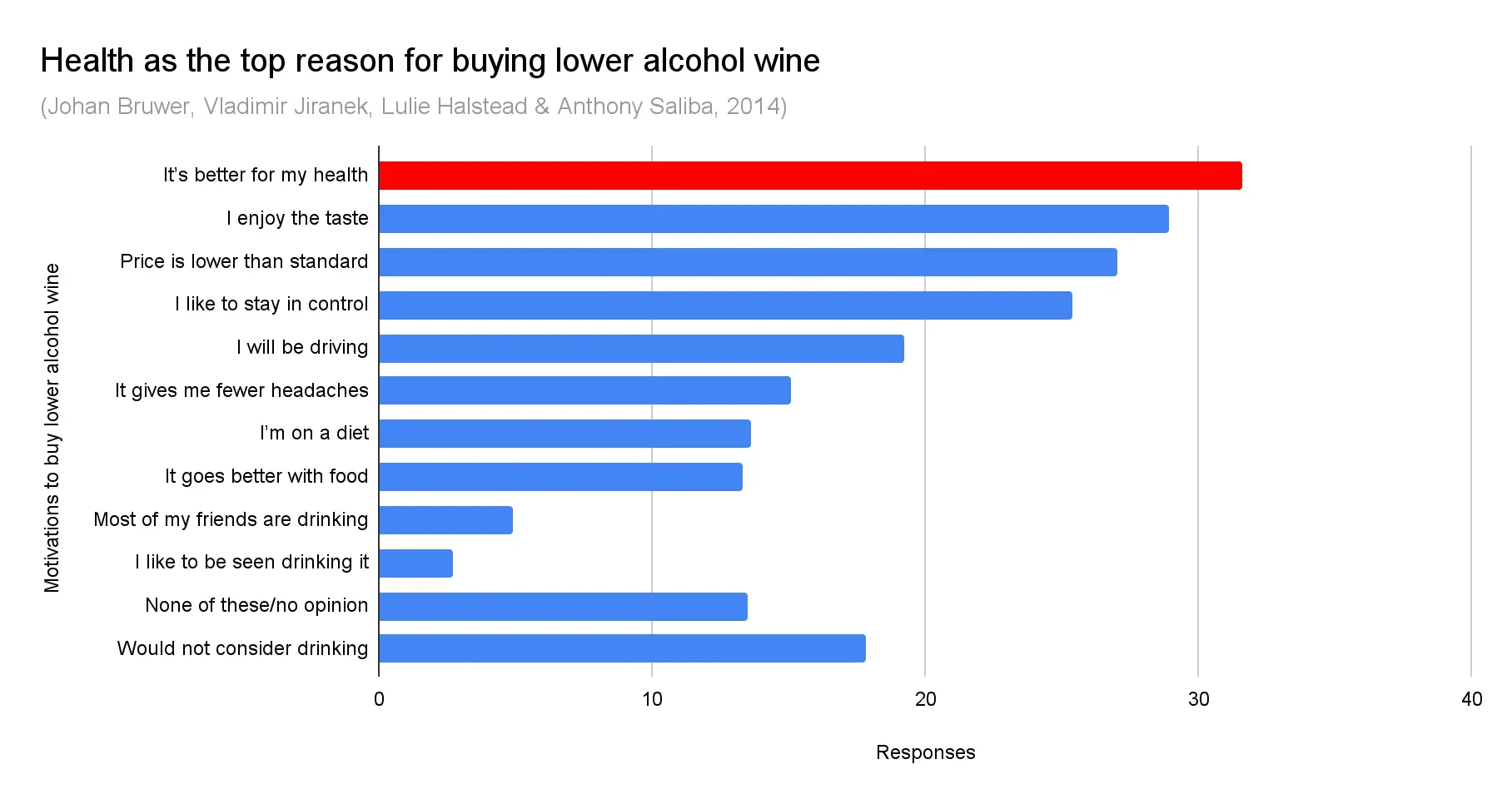

These health-conscious consumers are choosing NOLO as a substitute for traditional wine. A 2014 UK study found that the top reason for lower alcohol purchases was “it’s better for my health” (Bruwer et al., 2014).

Figure: UK motivations for lower-alcohol purchases.

Figure: UK motivations for lower-alcohol purchases.

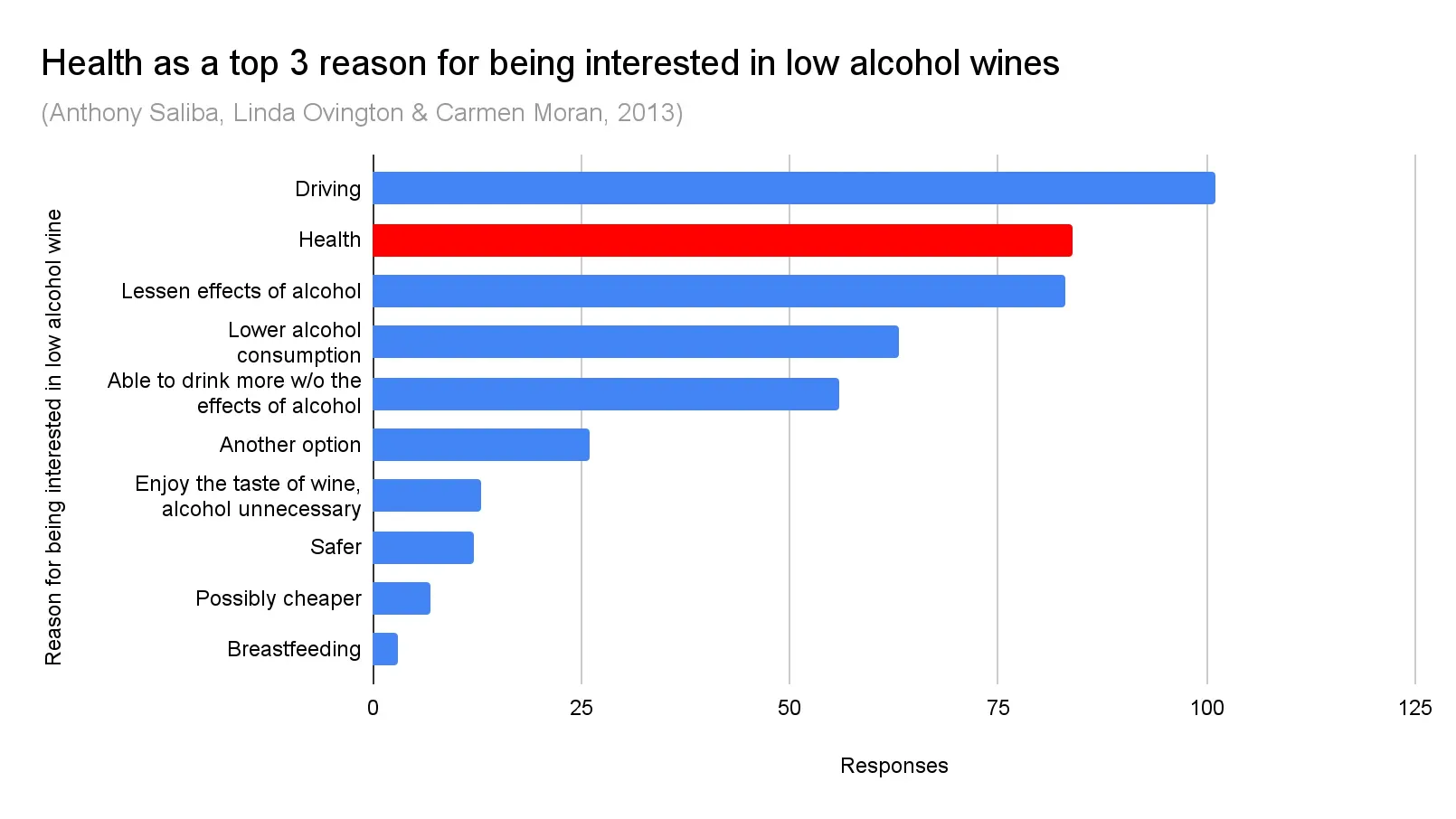

A separate 2013 Australian study supported this, with “health” being the second most common motivation for interest in NOLO (Saliba et al., 2013).

Figure: Australian motivations for NOLO interest.

Figure: Australian motivations for NOLO interest.

However, these demand influences on NOLO would not have been fulfilled, had product quality missed expectations. After all, NOLO is trending, not grape juice. Economic and technological factors have increased the supply of quality product offerings, past a tipping point of consumer acceptance.

Supply: quality improvements and production economics

From an economic perspective, NOLO’s high growth provides an attractive new profit opportunity, with industry experts discussing how “there’s money to be made” for producers (Carter, 2023). Companies that effectively target the younger demographic through enticing social media, graphics, and packaging have experienced notable success (Beaton, 2022). For example, Boisson, a NOLO retailer, increased its revenue 300% from 2021 to 2022, and recently raised venture funding from Pernod Ricard[^8] (Business Wire, 2023).

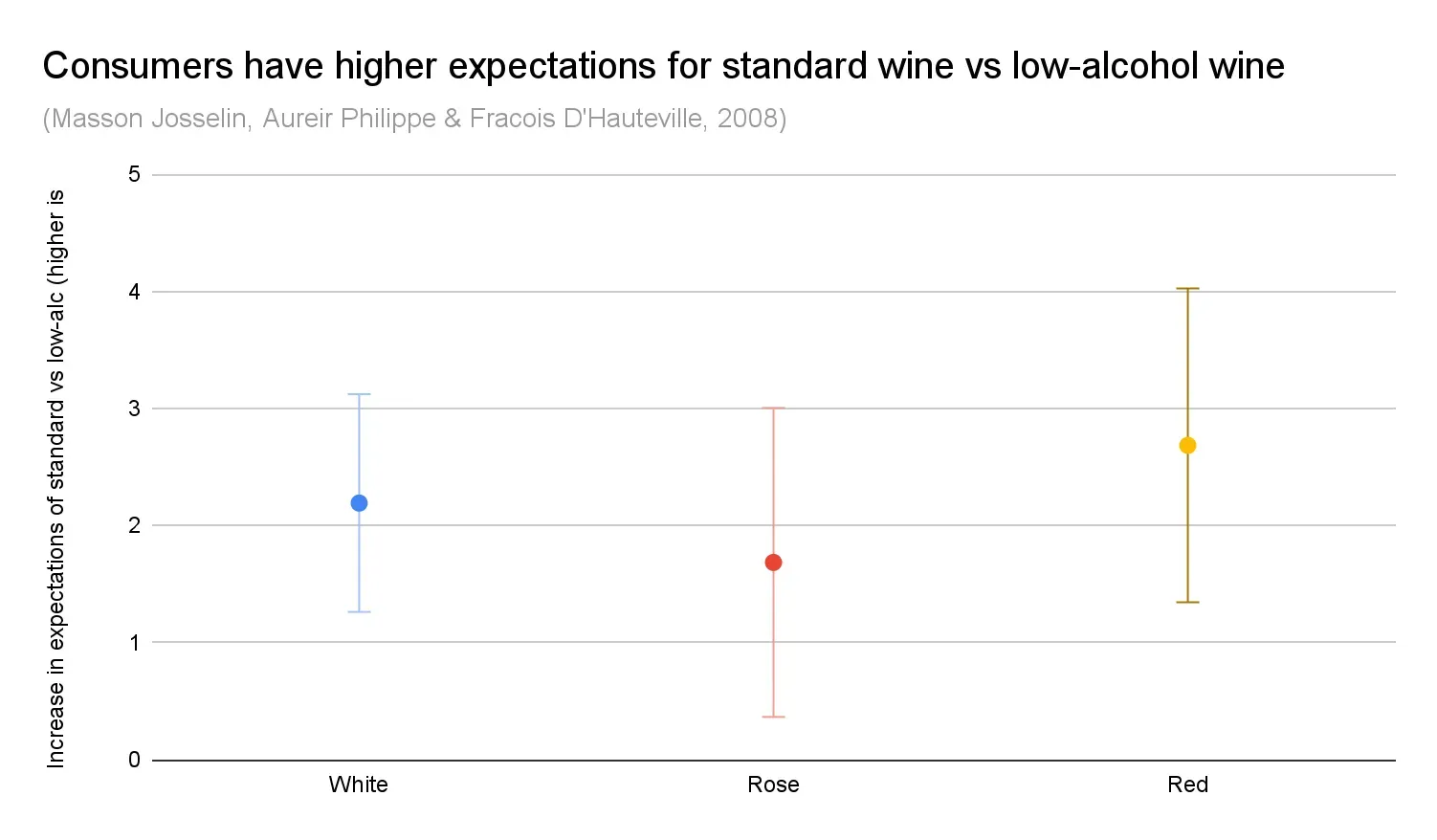

From a technology perspective, NOLO quality has improved greatly over the past 30 years. Historically, sweetness was used to compensate for the lack of ethanol, with sugar levels >40 g/L being common[^9] (Schulz et al., 2023). However, the typical drinker associates sweetness with lower quality cheap wine[^10], resulting in NOLO also being perceived as low quality even before being tasted (Josselin et al., 2008).

Figure: Sweetness perceptions and quality associations in NOLO.

Figure: Sweetness perceptions and quality associations in NOLO.

Modern technology has changed this. Lower processing temperatures and enhanced aroma adjustments have elevated product standards (Bucher et al., 2020; Pickering, 2010). While we will discuss the production process in detail in the next section, one such technique is the use of linalool, geranial, and isoamyl acetate extracts to enrich floral and fruity aromas in NOLO, where regulations are less strict than traditional wine[^11] (Ma et al., 2022).

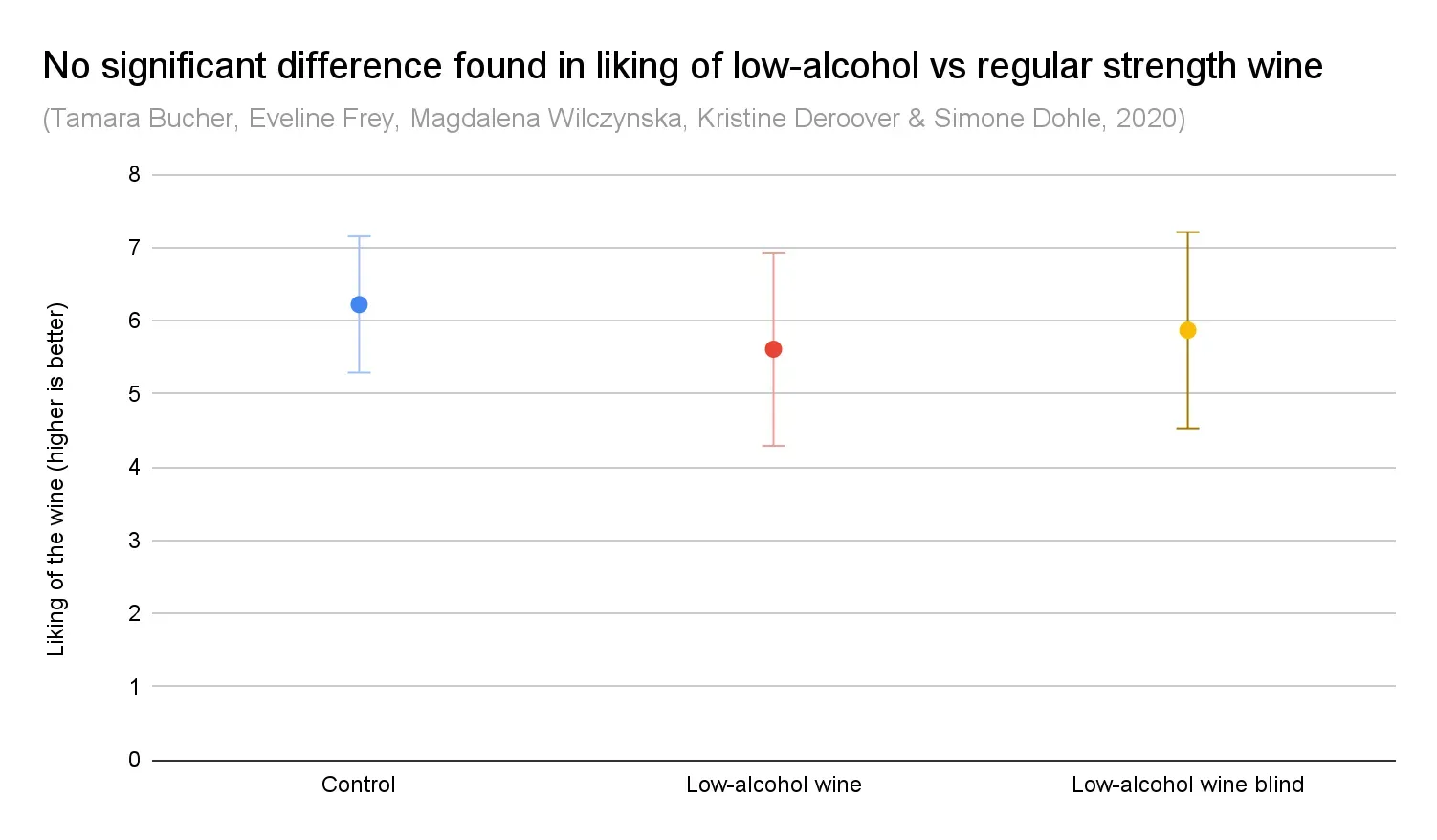

Today, NOLO wines are getting good reviews. For example, Wine Spectator’s review of Ariel Vineyards NOLO Chardonnay described it as “balanced, with varietal-specific aromas and flavors” (Napjus, 2022). A recent 2020 experiment also found no significant difference in how much participants liked NOLO vs standard wine[^12] (Bucher et al., 2020).

Figure: Comparative liking of NOLO vs standard wine.

Figure: Comparative liking of NOLO vs standard wine.

Summary of drivers

In summary, health has been the main demand driver for NOLO, with profit opportunities and technology improvements the main supply drivers. Although there are secondary reasons such as the affordability of lower taxed NOLO vs higher taxed traditional wine, social influencer campaigns, or a 2018 change in US tax law on higher alcohol wine driving alcohol driving alcohol reduction companies to seek new customers, the country agnostic growth in NOLO is due to the primary reasons above.

Reduce and reuse to make NOLO

This section outlines the main post-fermentation techniques used to reduce alcohol, emphasizing how process choices affect style, quality, and cost.

Unlike “natural wine”, NOLO requires massive human meddling. Instead of “nothing added, nothing taken”, NOLO opts for a “reduce and reuse” approach. Extreme opposites in winemaking philosophies; yet both have achieved success.

Whether red, white, rose, or sparkling, NOLO is typically made via two primary method families, each with subcategories:

-

Thermal distillation

a. Vacuum distillation

b. Spinning cone column

-

Semi-permeable membrane

a. Reverse osmosis

b. Osmotic distillation

Thermal distillation approaches

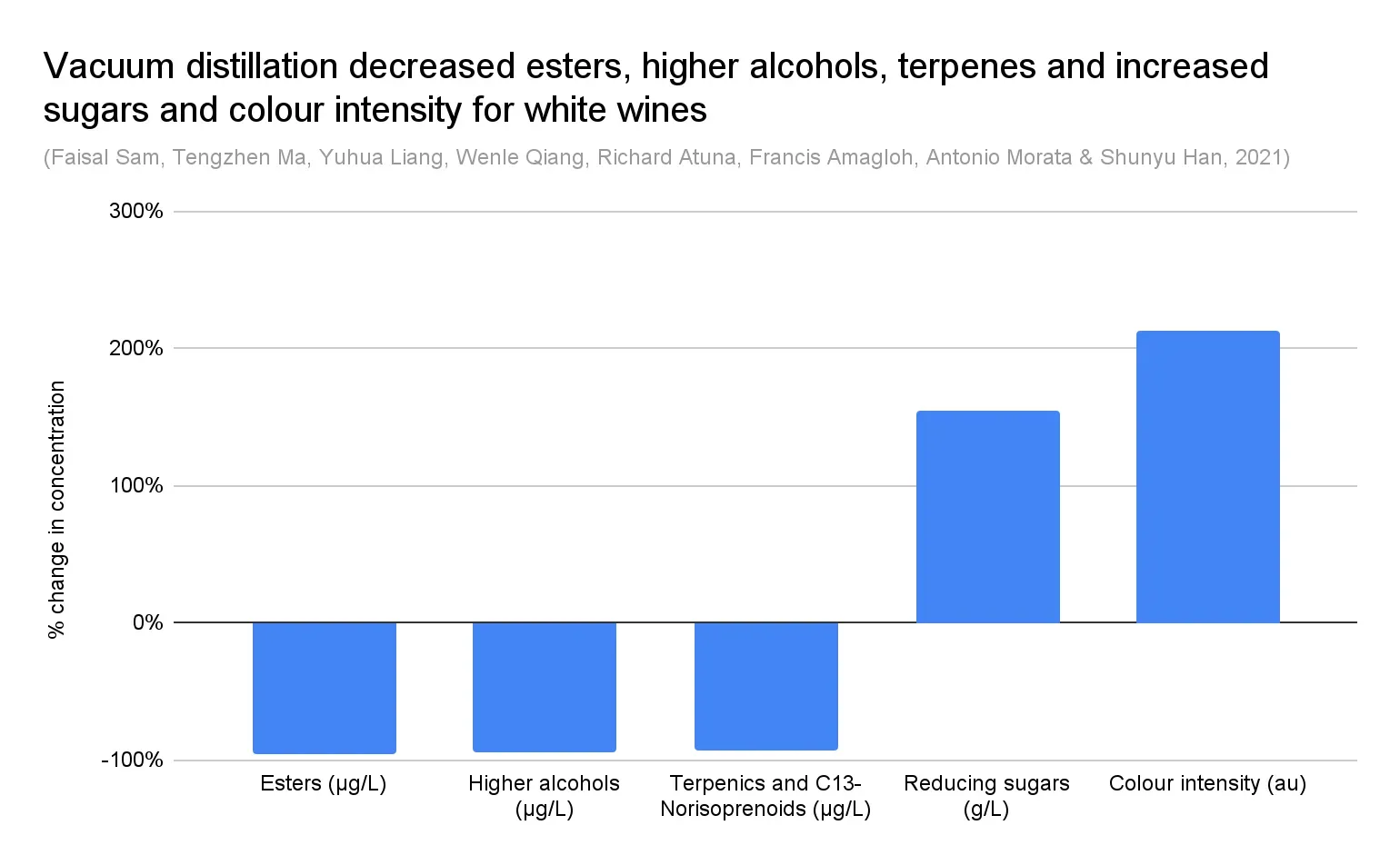

Thermal distillation processes require higher temperatures and cost more than membrane processes. Within this method, vacuum distillation is a common technique already used to adjust traditional wine alcohol levels at many wineries (Motta et al., 2017). Inside a tank, wine is heated at moderate temperatures (15-20C) under vacuum, which evaporates the ethanol. The ethanol vapour rises to the top of the tank, condensing as a distillate in a separate container, reducing the ABV of the tank’s liquid. Producers might opt to reuse volatile aromas from the distillate by capturing and adding them back after distillation (Ma et al., 2022).

![]() Figure: Vacuum distillation process schematic.

Figure: Vacuum distillation process schematic.

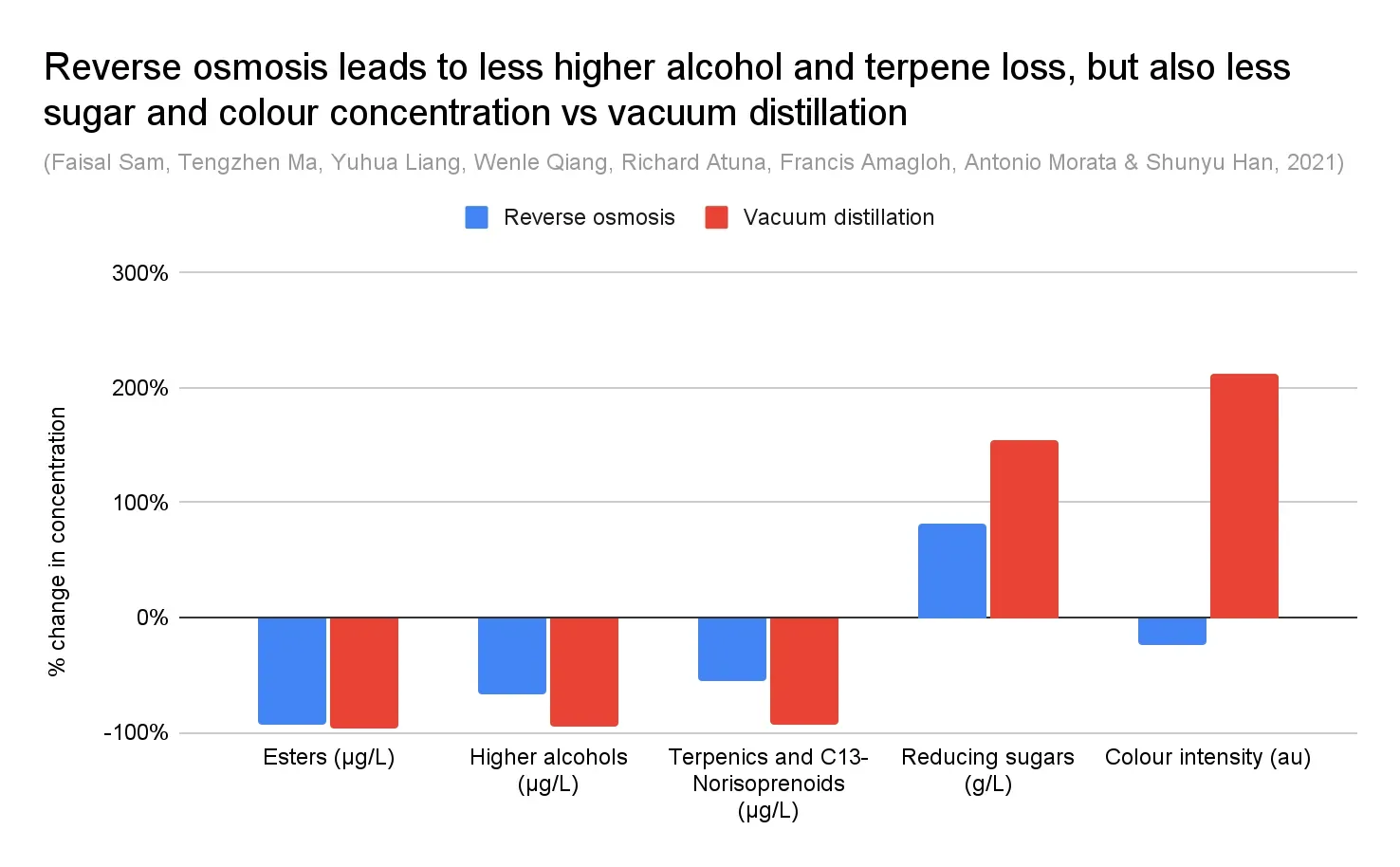

Vacuum distillation has a mixed effect on NOLO style and quality. It can significantly reduce many desirable volatile compounds, such as esters, higher alcohols, and terpenes. However, it can concentrate sugars and colour intensity (Sam et al., 2021). It is also quicker to reach a low final level of ABV.

Figure: Vacuum distillation outcomes and tradeoffs.

Figure: Vacuum distillation outcomes and tradeoffs.

Spinning cone column (SCC) is a modification of the vacuum distillation process that takes place in two stages to improve aroma retention. SCC consists of a central vertical shaft with convex cones[^13], rotating between other convex cones attached to the interior casing of the tank (Schmidtke et al., 2012). In the first stage, low vacuum pressure and moderate ~28C temperatures are used to recover desirable volatile aromas. In the second stage, higher vacuum pressure and ~38C temperatures are used to remove alcohol (Sam et al., 2021). The aromas from the first stage are reused by combining with the reduced alcohol liquid from the second stage, to create a product stylistically more similar to regular wine, and of higher quality than vacuum distillation.

In SCC, wine is pumped to the top of the tank, onto the 1st rotating cone attached to the central shaft. The spinning results in centrifugal force spraying a thin film of wine outwards onto the 1st fixed cone attached to the tank[^14]. The liquid trickles down this 1st fixed cone onto the 2nd rotating cone, and the process is repeated until it reaches the bottom of the column. While this is happening, a “stripping gas”[^15] is pumped in the bottom of the tank. As the gas rises to the top, it picks up volatile aromas or ethanol through mass transfer. Fins attached to the cones increase turbulence and hence effectiveness of the process. This allows for both a reduction in alcohol, and a reuse of aromas later on (Schmidtke et al., 2012).

![]() Figure: Spinning cone column process schematic.

Figure: Spinning cone column process schematic.

SCC stands out for its ability to recover desirable aromas with both high efficiency and minimal passes, leading to higher quality NOLO. While it is favoured by producers for its quality outcomes, the downside includes the substantial capital costs for equipment and the requirement for specialised operational expertise, implying higher production volumes are required to make it economical.

For example, BevZero, an alcohol reduction provider, quotes $1-2mm setup costs for SCC (Beverage Trade Network, 2023). Producers may outsource this step to providers such as BevZero, similar to how some sparkling winemakers delegate parts of the production process (BevZero, 2023; Oztruk & Anli, 2015). However, this may not be possible in countries where expected production volumes are too low to justify investment, such as Austria (Gentile et al., 2023).

Membrane-based approaches

Membrane processes typically require lower temperatures but more passes than thermal processes. Reverse osmosis (RO) uses a hydrophilic semi-permeable membrane under high pressure but low 1-5C temperatures. High pressure on the side with a higher concentration solution causes a reverse of the typical osmosis process, resulting in even higher concentrations on that side. This filters out smaller ethanol and water molecules from the base wine over multiple tangential passes through the membrane. The ethanol and water mixture can be further separated through distillation, allowing for reuse of the water in the process (Ma et al., 2022).

![]() Figure: Reverse osmosis process schematic.

Figure: Reverse osmosis process schematic.

RO benefits include aroma retention due to the low operating temperatures, lower capital and operating costs than thermal distillation (therefore possibly lower prices), and being a “clean” technology since the ethanol and water can be reused after extraction. For example, it has a lower rate of higher alcohol and terpene loss compared to vacuum distillation, implying a higher quality NOLO that is stylistically more similar to regular wine (Sam et al., 2021).

RO drawbacks include the multiple passes required for the alcohol reduction, recurring costs for membrane replacement, and legal uncertainties regarding the re-addition of water in the production process, since adding water to wine is banned in some countries (Ma et al., 2022).

Figure: Reverse osmosis impacts on style and aroma retention.

Figure: Reverse osmosis impacts on style and aroma retention.

Osmotic distillation[^16] (OD) also uses a membrane for alcohol reduction. Differential vapour pressure on both sides of a hydrophobic membrane causes ethanol to evaporate on one side, diffuse across the membrane, and then condense on the other side with the help of a “stripping gas”[^17] (Schmidtke et al., 2012).

![]() Figure: Osmotic distillation process schematic.

Figure: Osmotic distillation process schematic.

Compared to RO, OD requires lower pressures and temperatures. However, longer processing time is required. OD effect on style and quality is uncertain, with conflicting studies citing minimal aroma compound loss or adverse effects on volatile aromas, depending on the amount of alcohol reduced (Ma et al., 2022; Schmidtke et al., 2012).

Other post fermentation options in NOLO production include nanofiltration, pervaporation, or multistage systems that combine multiple methods. However, these are not as widely used commercially due to cost or lack of research, and we will not be discussing these further (Ma et al., 2022; Schmidtke et al., 2012).

Comparative summary

+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+ | Removal | Pros | Cons | Sample | | method | | | producers | +-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+ | Vacuum | - Good for | - Bad for style | - Weingut Leitz | | distillation | sugar and | and quality | | | | colour | due to | - Thomson & | | | concentration | reduction of | Scott | | | | esters, | | | | - Cheap; many | higher | - St Regis | | | wineries | alcohols, | | | | already have | terpenes | | | | the equipment | | | | | | | | | | - Lower price | | | | | implication | | | +-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+ | Spinning cone | - Good for | - High $1-2mm | - Giesen | | column | style and | capital costs | | | | quality due | | - Fre Wines | | | to high aroma | - Specialised | | | | recovery | expertise | - Weingut Leitz | | | | required | | | | - Faster | | | | | processing | - Higher price | | | | time as fewer | implication | | | | passes | | | | | required | | | +-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+ | Reverse Osmosis | - Good for | - Legal | - Ariel | | | style and | uncertainty | vineyards | | | quality due | in countries | | | | to aroma | where water | | | | retention | cannot be | | | | | added to | | | | - Lower capital | wine; grape | | | | and operating | must might be | | | | costs than | a workaround | | | | thermal | | | | | distillation | - Slower | | | | | processing | | | | - Lower price | time than | | | | implication | thermal | | | | | distillation | | | | - “Clean” | as multiple | | | | technology | passes | | | | | required | | | | | | | | | | - Recurring | | | | | replacement | | | | | costs when | | | | | membranes | | | | | fail | | +-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+-----------------+ | Osmotic | - Possibly good | - Even slower | - None | | distillation | for style and | processing | disclosed | | | quality due | time than RO | publicly | | | to aroma | due to lower | | | | retention, | temperature | | | | but more | and pressure | | | | research | | | | | required | | | | | | | | | | - Energy and | | | | | cost savings | | | | | due to lower | | | | | temperature | | | | | and pressure | | | | | requirements | | | +=================+=================+=================+=================+

(Alexandra, 2021; LeBeau, 2018; Mowery, 2021; VE Refinery, 2022)

NOLO has ample room to grow

This section considers market scale, headwinds, and practical responses, before moving to the author’s perspective on category positioning.

NOLO’s current total market revenue of $2bn is a fraction of the total $173bn wine market, implying future growth potential (Fact.MR, 2022; Statista, 2023). Though there are some headwinds ahead, the tailwinds for this category should continue to propel faster growth than the overall wine market. In addition, I would like to propose an alternative approach to NOLO marketing.

Headwinds

Climate change, costs of production, and consumer perception are the three main headwinds to NOLO growth.

Climate change typically results in higher alcohol levels in wine, the reverse of NOLO aims. Sunny winemaking regions have seen alcohol content rise by ~2% ABV over the past 30 years due to the higher sugar concentration at harvest (Goold et al., 2017).

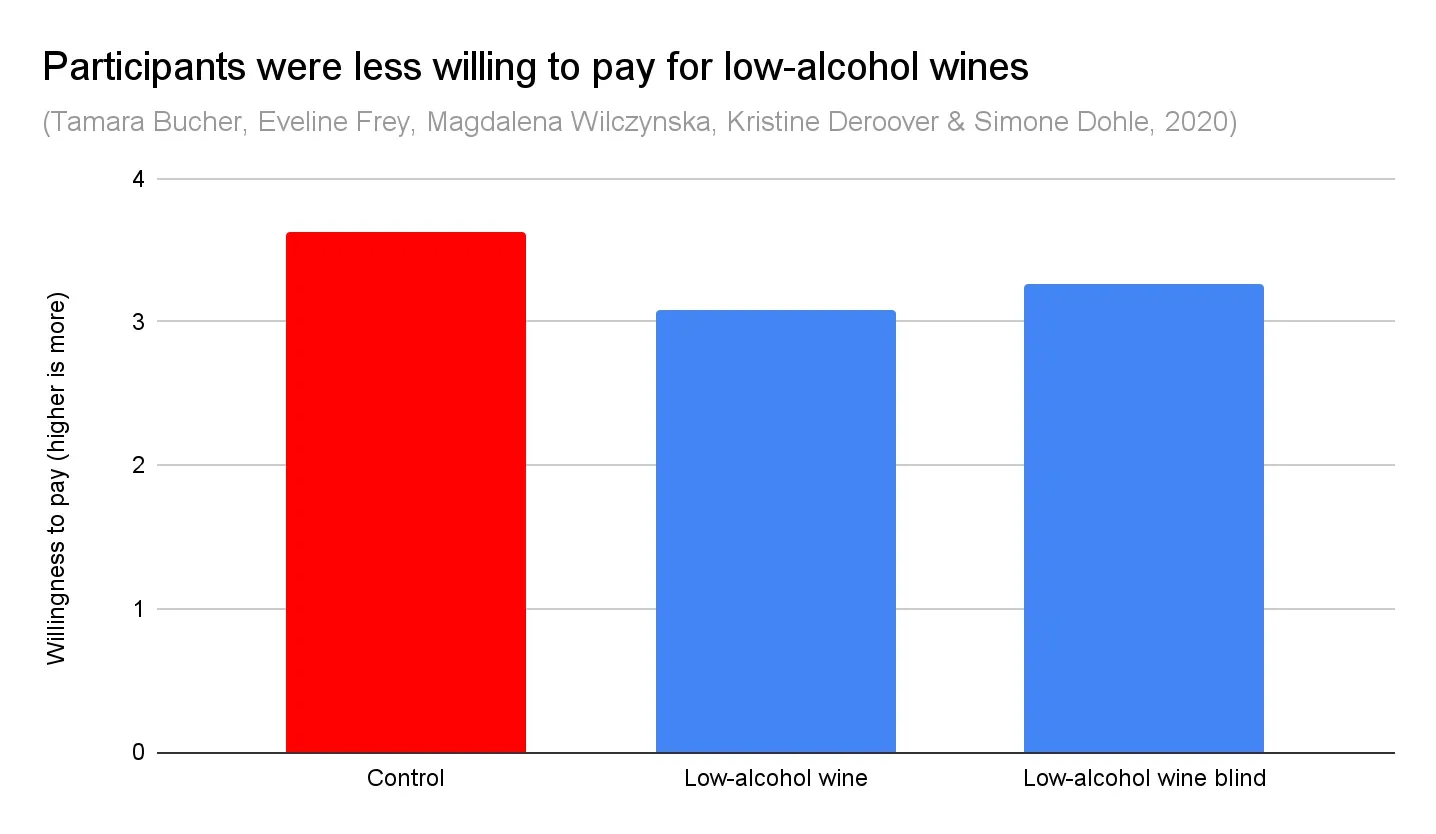

The increased production costs associated with crafting NOLO from quality base wine suggest the need for higher pricing. However, it remains uncertain whether consumers are willing to pay more for a product with less alcohol. A 2020 study indicated reduced consumer willingness to pay for NOLO, supported by a NielsenIQ report revealing an average US NOLO price of $6.84 vs $11.01 for traditional wine (Bucher et al., 2020; NielsenIQ, 2023). In contrast, six of the top eight best-selling NOLO products on Boisson are priced >$20, above the typical cost of traditional wines[^18] (Boisson, 2023).

Figure: NOLO pricing relative to traditional wine benchmarks.

Figure: NOLO pricing relative to traditional wine benchmarks.

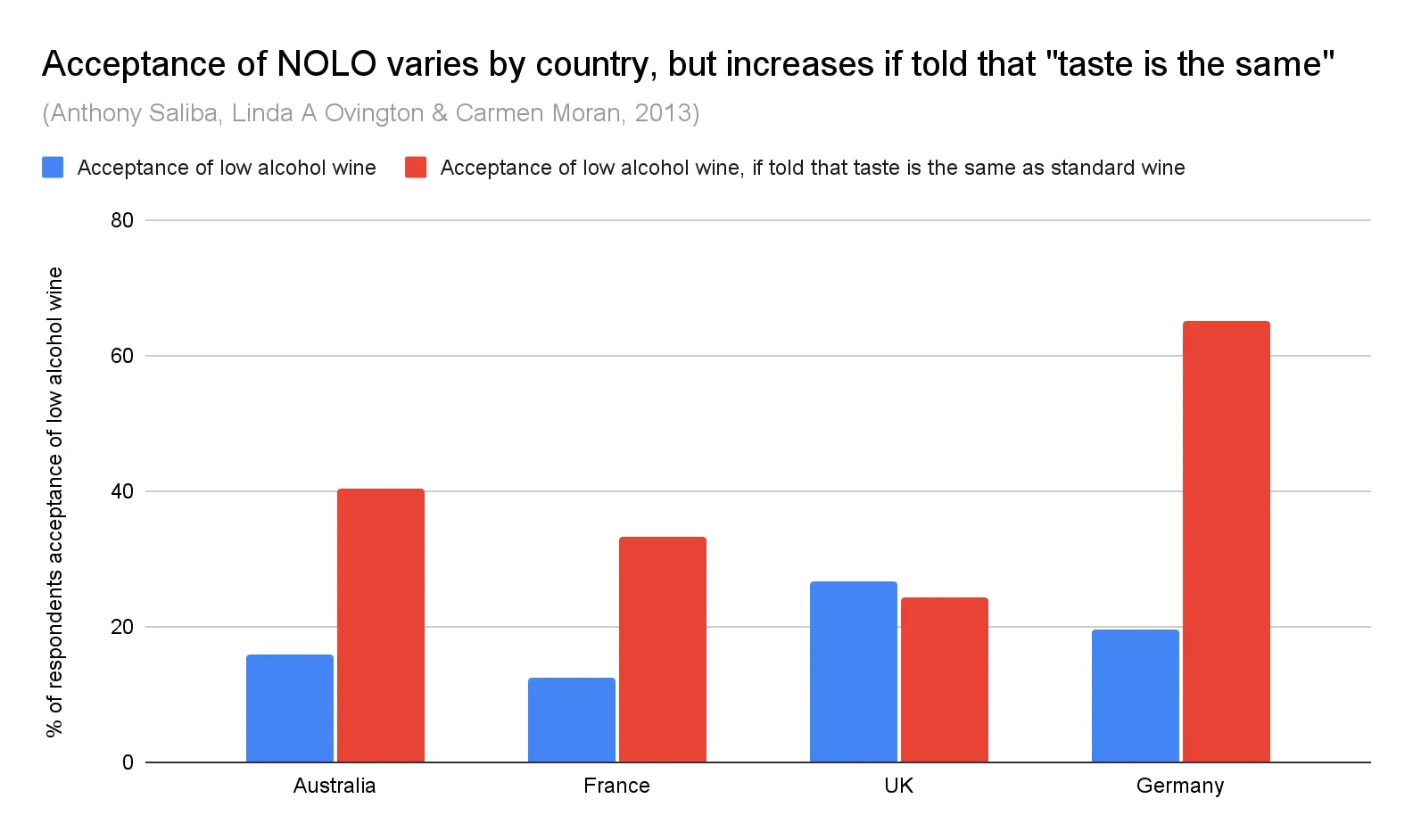

Consumer perception that NOLO products are inferior is also an obstacle. Acceptance of NOLO varies by country, with people adjusting their attitudes only when assured that taste quality would be the same (Saliba et al., 2013).

Figure: NOLO acceptance varies when quality parity is emphasized.

Figure: NOLO acceptance varies when quality parity is emphasized.

Mitigation options

Producers have multiple options to mitigate the above risks. In the vineyard, planting varieties that naturally make lower alcohol wines (e.g. Furmint), harvesting earlier, or selecting sites of formerly marginal areas benefiting from climate change (e.g. UK) could increase NOLO production resilience (Frank, 2022).

In the winery, usage of glucose oxidase to reduce fermentable sugars or new yeast strains selected for lower ethanol production[^19] could reduce costs in the future. For instance, Athletic Brewing Co has successfully prevented ethanol generation during fermentation for its beers (Mazzeo, 2022). This remains a field of ongoing research due to the complexity of yeast biology in quality wine production (Goold et al., 2017; Schmidtke et al., 2012).

To change consumer perception, producers might consider partnering with the public sector for additional marketing impact. Governments or public health agencies could be open to promoting NOLO, if it helps reduce overall alcohol consumption and improve health outcomes. Having additional funding from other sources will help NOLO reach a larger top of the funnel audience. For example, the UK Department of Health and Social Care is committed to supporting the NOLO industry to increase product availability by 2025 (Gov.UK, 2023).

Since NOLO is not subject to the same restrictions as wine, alternative sales channels can also help with growth. For example, US regulations technically consider the ethanol content destroyed after the NOLO process, placing it under Food and Drug Administration rather than Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau jurisdiction. This makes it possible to sell and offer tastings of NOLO in grocery stores, an attractive marketing opportunity (Beverage Trade Network, 2023).

Positioning and outlook

NOLO technology is likely to improve over time; health conscious attitudes towards alcohol are unlikely to reverse in the short term. Together with the options above, it is likely NOLO continues growing faster than the traditional wine market.

I also believe that current NOLO marketing is missing the point. Rather than harping on the association with wine, NOLO should intentionally brand itself as a standalone category. Consumers do not care that the product was originally made from wine or about the technological breakthroughs behind it. Instead, they want something that tastes good and makes them feel good about their lifestyle choices.

Here, NOLO can learn from sparkling and natural wine. Both fall under the broader category of wine but are regarded as distinct products. Consumers don’t object to the effervescence in their Champagne or the haziness in their natural wine; these characteristics are embraced within their respective styles. Similarly, NOLO should offer a distinct style rather than mimic wine. Transforming into a beverage that people enjoy on its own will also alleviate the current challenges associated with pairing NOLO with food.

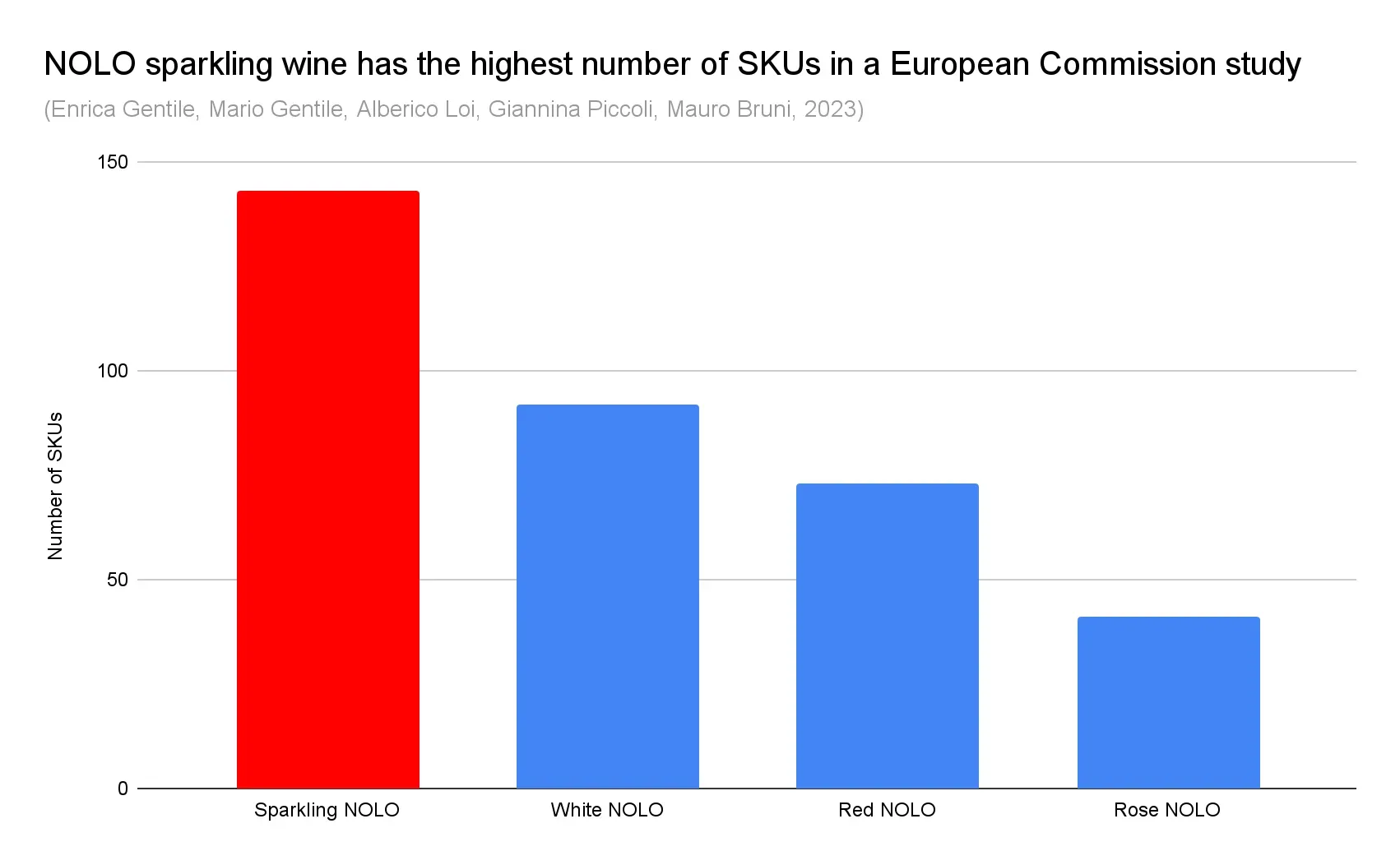

Especially noteworthy is the potential rise of a sparkling NOLO product promoted based on its inherent qualities, akin to the recent surge in the hard seltzer market (Grand View Research, 2023). The effervescence can enhance the perception of quality, mask potential faults, and distinguish it from traditional wine. Given positive reviews for sparkling NOLO products (e.g. Thomson & Scott Noughty), it’s not surprising that the majority of current NOLO offerings are of the sparkling variety (Farrell, 2023; Gentile et al., 2023).

Figure: Sparkling NOLO prominence within current offerings.

Figure: Sparkling NOLO prominence within current offerings.

A hundred years on from Prohibition, the Temperance movement has come and gone, but perhaps a tempered temperance, NOLO movement is on the rise. Health concerns have increased demand for NOLO, with technological and economic factors improving supply.

As these trends mutually reinforce each other in a growth loop, I anticipate sustained and even accelerated growth in the NOLO category. Furthermore, I foresee the ascent of a sparkling NOLO product solely driven by its exceptional taste, breaking free from the limitations of being solely a wine derivative, and evolving to a formidable standalone brand.

References

References

Sources cited in the essay are listed below.

Alcohol Change UK. (2023, - -). The Dry January story. Alcohol Change UK. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://alcoholchange.org.uk/help-and-support/managing-your-drinking/dry-january/about-dry-january/the-dry-january-story

Alexandra. (2021, June 14). Wine-Recipe | Leitz Eins-Zwei-Zero range makes responsible drinking a pleasure. Carrots and Tigers. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://carrotsandtigers.com/2021/06/14/wine-recipe-leitz-eins-zwei-zero-range-makes-responsible-drinking-a-pleasure/

Anderson, P., Kokole, D., & Llopis, E. J. (2021). Production, Consumption, and Potential Public Health Impact of Low- and No-Alcohol Products: Results of a Scoping Review. Nutrients, 13(9), 3153. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093153

Beaton, K. (2022, August 15). Young Adults Embracing No- and Low-Alcohol Products. The Food Institute. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://foodinstitute.com/focus/young-adults-embracing-no-and-low-alcohol-products/

Beverage Trade Network. (2023, March 2). Non Alcoholic Beverages Explained | Matthew Hughes. YouTube. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6hL20PwLzQ

Beverage Trade Network. (2023, July 16). What is Non-alcoholic Wine and How is it made | Inside The Drinks Business. YouTube. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAZ3hTN_lz4

BevZero. (2023, June 30). Choosing The Right Dealcoholization Method. BevZero. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://bevzero.com/choosing-dealcoholization-method/

Boisson. (2023). Best Selling Products — Boisson. Boisson. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://boisson.co/collections/best-selling-products

Brand, D., Saisana, M., Rynn, L., Pennoni, F., Lowenfels, A., & Hay, P. (2007, April 24). Comparative Analysis of Alcohol Control Policies in 30 Countries. PLoS Med, 4(4), -. PubMed Central. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040151

Bruwer, J., Jiranek, V., Halstead, L., & Saliba, A. (2014, July). Lower alcohol wines in the UK market: Some baseline consumer behaviour metrics. British Food Journal, 116(7), 1143-1161. ResearchGate. 10.1108/BFJ-03-2013-0077

Bruwer, J., Saliba, A., & Miller, B. (2011, January). Consumer behaviour and sensory preference differences: Implications for wine product marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 5-18. ResearchGate. 10.1108/07363761111101903

Bucher, T., Deroover, K., & Stockley, C. (2018). Low-Alcohol Wine: A Narrative Review on Consumer Perception and Behaviour. Beverages, 4(4), 82. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4040082

Bucher, T., Deroover, K., & Stockley, C. (2019, June). Production and Marketing of Low-Alcohol Wine. Advances in Grape and Wine Biotechnology, -(-), -. ResearchGate. 10.5772/intechopen.87025

Bucher, T., Frey, E., Wilczynska, M., Deroover, K., & Dohle, S. (2020, May 19). Consumer perception and behaviour related to low-alcohol wine: do people overcompensate? Public Health Nutrition, 23(11), 1939-1947. PubMed Central. 10.1017/S1368980019005238

Business Wire. (2023, September 27). Non-Alcoholic Retailer Boisson Announces New CEO; Receives New Funding From Convivialité Ventures and Connect Ventures. Business Wire. Retrieved December 31, 2023, from https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20230927406605/en/Non-Alcoholic-Retailer-Boisson-Announces-New-CEO-Receives-New-Funding-From-Convivialit%C3%A9-Ventures-and-Connect-Ventures

Carter, F. (2023, November 28). 8 Reasons to Get Excited About the No-Alcohol Category. Meininger’s International. https://www.meiningers-international.com/wine/insights/8-reasons-get-excited-about-no-alcohol-category

Corona, O., Liguori, L., Albanese, D., Matteo, M. D., Cinquanta, L., & Russo, P. (2019, October 3). Quality and volatile compounds in red wine at different degrees of dealcoholization by membrane process. European Food Research and Technology Aims and scope Submit manuscript, 245(-), 2601-2611. Springer Link. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-019-03376-z

Drizly. (2023, - -). Non-Alcoholic Wine, Beer, and Spirits. BevAlc Insights. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://bevalcinsights.com/category-on-the-rise-non-alcoholic-wine-beer-and-spirits/

Fact.MR. (2022, December -). Non-Alcoholic Wine Market Outlook (2023-2033). Non-Alcoholic Wine Market. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.factmr.com/report/4532/non-alcoholic-wine-market

Farrell, N. (2023, March 10). The 8 Best Nonalcoholic Wines of 2023 | Reviews by Wirecutter. The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/reviews/best-nonalcoholic-wines/

Forbes, S., Cohen, D., & Dean, D. (2010, January). Women and wine: analysis of this important market segment. ResearchGate. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/50600553_Women_and_wine_analysis_of_this_important_market_segment

Frank, C. (2022, January 17). The No- and Low-Alcohol Wine Category is Booming---and Retailers Should Pay Attention. SevenFifty Daily. https://daily.sevenfifty.com/the-no-and-low-alcohol-wine-category-is-booming-and-retailers-should-pay-attention/

Gallup. (2023, Jul). Alcohol and Drinking | Gallup Historical Trends. Gallup News. Retrieved December 31, 2023, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/1582/alcohol-drinking.aspx

Gentile, E., Gentile, M., Loi, A., Piccoli, G., & Bruni, M. (2023, March 2). Study on low/no alcohol beverages - Publications Office of the EU. Publications Office of the EU. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/bc7b29d4-b7e7-11ed-8912-01aa75ed71a1

Google. (2023, December 04). Google Trends. Google Trends. Retrieved December 04, 2023, from https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2008-12-04%202023-12-04&q=no%20alcohol%20wine,low%20alcohol%20wine&hl=en

Goold, H., Kroukamp, H., Williams, T., Paulsen, I., Varela, C., & Pretorius, I. (2017, January 13). Yeast’s balancing act between ethanol and glycerol production in low-alcohol wines. Microbial Biotechnology, 10(2), 264-278. Applied Microbiology International. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12488

Gov.UK. (2023, September 28). Updating labelling guidance for no and low-alcohol alternatives: consultation. GOV.UK. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/updating-labelling-guidance-for-no-and-low-alcohol-alternatives/updating-labelling-guidance-for-no-and-low-alcohol-alternatives-consultation

Grand View Research. (2023, - -). Hard Seltzer Market Size, Share And Trends Report, 2030. Grand View Research. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/hard-seltzer-market

Gutierrez, A. R., Portu, J., Lopez, R., Garijio, P., Gonzalez-Arenzana, L., & Santamaria, P. (2023, June 10). Carbonic maceration vinification: A tool for wine alcohol reduction. Food Chemistry, -(-), -. PubMed. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136558

Han, B., Daniel, M. G., Park, E., & Piscopo, K. (2020, - -). Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. SAMHSA. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29394/NSDUHDetailedTabs2019/NSDUHDetailedTabs2019.pdf

International Food Information Council Foundation. (2018, - -). 2018 Food and Health Survey Report. Food Insight. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018-FHS-Report-FINAL.pdf

Josselin, M., Philippe, A., & D’Hauteville, F. (2008, Aug). Effects of non-sensory cues on perceived quality: The case of low-alcohol wine. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 20(3). ResearchGate. 0.1108/17511060810901037

King, E. S., Dunn, R. L., & Heymann, H. (2013, April). The influence of alcohol on the sensory perception of red wines. Food Quality and Preference, 28(1), 235-243. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.08.013

LeBeau, A. (2018, January 26). Non-Alcoholic Wine - Because sometimes you have to. SpitBucket. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://spitbucket.net/2018/01/26/non-alcoholic-wine-sometimes/

Lechmere, A. (2012, February 16). Consumers across three continents prefer lower alcohol wines: Prowein - Decanter. Decanter Magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/consumers-across-three-continents-prefer-lower-alcohol-wines-prowein-32578/

Liguori, L., Albanese, D., Crescitelli, A., Matteo, M. D., & Russo, P. (2019, June 13). Impact of dealcoholization on quality properties in white wine at various alcohol content levels. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(-), 3707-3720. Springer Link. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-019-03839-x

Looze, M. d., Raaijmakers, Q., Bogt, T. t., Bendtsen, P., Farhat, T., Ferreira, M., Godeau, E., Kuntsche, E., Molcho, M., Pförtner, T.-K., Simons-Morton, B., Vieno, A., Vollebergh, W., & Pickett, W. (2015, March 20). Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(Suppl 2), 69-72. PubMed Central. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv031

Loy, J. K., Seitz, N.-N., Bye, E. K., Raitasalo, K., Soellner, R., Torronen, J., & Kraus, L. (2021, November 1). Trends in alcohol consumption among adolescents in Europe: Do changes occur in concert? Drug and alcohol dependence, 228(-), -. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109020

Ma, T.-Z., Sam, F. E., & Zhang, B. (2022, June 30). Low-Alcohol and Nonalcoholic Wines: Production Methods, Compositional Changes, and Aroma Improvement. Recent Advances in Grapes and Wine Production - New Perspectives for Quality Improvement, -(-), -. IntechOpen. 10.5772/intechopen.105594

Masson, J., Aurier, P., & d’hauteville, F. (2008, August 22). Effects of non‐sensory cues on perceived quality: the case of low‐alcohol wine. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 20(3), 215-229. Emerald Insight. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511060810901037

Mazzeo, J. (2022, July 25). The Science Behind Non-Alcoholic Beer and Wine Production. SevenFifty Daily. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://daily.sevenfifty.com/the-science-behind-non-alcoholic-beer-and-wine-production/

Motta, S., Guaita, M., Petrozziello, M., Ciambotti, A., Panero, L., Solomita, M., & Bosso, A. (2017, April 15). Comparison of the physicochemical and volatile composition of wine fractions obtained by two different dealcoholization techniques. Food Chemistry, 221(-), 1-10. ScienceDirect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.046

Mowery, L. (2021, September 22). Is It Possible To Make A Nonalcoholic ‘Grand Cru’ Quality Wine? This Winemaker Says Yes. Forbes. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/lmowery/2023/02/22/is-it-possible-to-make-a-nonalcoholic-grand-cru-quality-wine-this-winemaker-says-yes/?sh=2edea2f13c83

Napjus, A. (2022, January 7). Are There Any Good Non-Alcoholic Wines? Wine Spectator. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.winespectator.com/articles/are-there-any-good-non-alcoholic-wines

The New Consumer & Coefficient Capital. (2022, December 2). Consumer Trends 2023. The New Consumer. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://newconsumer.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Consumer-Trends-2023.pdf

Nielsen. (2021, October 28). An inside look into the global consumer health and wellness revolution. NIQ. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/report/2021/an-inside-look-into-the-2021-global-consumer-health-and-wellness-revolution/#chapter-1

NielsenIQ. (2023, October 30). The rise of non-alcoholic. NielsenIQ. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://nielseniq.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2022/10/32634-beval-non-alc-infographic-d02-1.jpg

NutriSystem. (2023, March 2). OVER 70% OF AMERICANS ARE MORE CONSCIOUS OF THEIR PHYSICAL HEALTH POST-PANDEMIC. The Leaf. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://leaf.nutrisystem.com/americans-health-conscious-post-pandemic

OIV. (2012). RESOLUTION OIV-ECO 432-2012. OIV. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1901/oiv-eco-432-2012-en.pdf

OIV. (2012). RESOLUTION OIV-ECO 433-2012. OIV. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1902/oiv-eco-433-2012-en.pdf

OIV. (2012). RESOLUTION OIV-OENO 394A-2012. OIV. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1431/oiv-oeno-394a-2012-en.pdf

OIV. (2012). RESOLUTION OIV-OENO 394B-2012. OIV. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1432/oiv-oeno-394b-2012-en.pdf

Our World in Data. (2017). Alcohol Consumption. Our World in Data. Retrieved December 31, 2023, from https://ourworldindata.org/alcohol-consumption#total-alcohol-consumption-over-the-long-run

Oztruk, B., & Anli, E. (2015, Feb 4). Different techniques for reducing alcohol levels in wine: A review. BIO Web of Conferences, 3, 8. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20140302012

Pickering, G. (2010, August 4). Low- and Reduced-alcohol Wine: A Review. Journal of Wine Research, 11(2), 129-144. Taylor & Francis Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571260020001575

Reiley, L., Morrison, N., & Lacap, B. (2023, March 24). Could nonalcoholic wine be the toast of the town? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/03/25/nonalcoholic-wine/

Rossow, I., Bye, E. K., Moan, I. S., & Tchounwou, P. B. (2022, July). The Declining Trend in Adolescent Drinking: Do Volume and Drinking Pattern Go Hand in Hand? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7965. PubMed Central. 10.3390/ijerph19137965

Rossow, I., & Storvoll, E. (2013, December 12). Long-term trends in alcohol policy attitudes in Norway. Drug and Alcohol review, 33(3), 220-226. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12098

Saliba, A., Ovington, L., & Moran, C. (2013, March). Consumer demand for low-alcohol wine in an Australian sample. International Journal of Wine Research, 1(5), -. ResearchGate. 10.2147/IJWR.S41448

Saliba, A., Ovington, L., Moran, C. C., & Bruwer, J. (2013, March/April -). Consumer attitudes to low alcohol wine: an Australian sample. -. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.marketingscience.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Saliba-2013-WVJ-6595.pdf

Sam, F. E., Ma, T., Liang, Y., Qiang, W., Atuna, R. A., Amagloh, F. K., Morata, A., & Han, S. (2021, December 1). Comparison between Membrane and Thermal Dealcoholization Methods: Their Impact on the Chemical Parameters, Volatile Composition, and Sensory Characteristics of Wines. Membranes, 11(12), 957. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11120957

Sam, F. E., Ma, T.-Z., Salifu, R., Wang, J., Jiang, Y.-M., Zhang, B., & Han, S.-Y. (2021, October 18). Techniques for Dealcoholization of Wines: Their Impact on Wine Phenolic Composition, Volatile Composition, and Sensory Characteristics (C. Duan & Y. Lan, Eds.). Foods, 10(10), 2498. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102498

Schmidtke, L. M., Blackman, J. W., & Agboola, S. O. (2012, January). Production Technologies for Reduced Alcoholic Wines. Journal of Food Science, 77(1), R25-R41. IFT. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02448.x

Schulz, F. N., Farid, H., & Hanf, J. H. (2023, August 30). The Lower the Better? Discussion on Non-Alcoholic Wine and Its Marketing. Dietetics, 2(3), 278-288. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics2030020

Schulz, F. N., & Hanf, J. (2023, Sep 12). European Alcohol Policy Is Coming for Wine. Meininger’s International. Retrieved December 31, 2023, from https://www.meiningers-international.com/wine/academic-papers-wine/european-alcohol-policy-coming-wine

Statista. (2023, November -). Wine - Worldwide. Statista. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/alcoholic-drinks/wine/worldwide

Stockley, C., Taylor, A., Montgomeri, A., & Grande, E. D. (2017, Mar 13). Changes in wine consumption are influenced most by health: results from a population survey of South Australians in 2013. International Journal of Wine Research, 9(-), 13-22. Taylor & Francis Online. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWR.S126417

Texas Health. (2023, April 25). Study Shows Younger Generations Are More Health-Conscious Than Previous Generations. Texas Health Resources. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.texashealth.org/areyouawellbeing/Health-and-Well-Being/Study-Shows-Younger-Generations-Are-More-Health-Conscious-Than-Previous-Generations

VE Refinery. (2022, June 29). How is the alcohol removed from wine? |VE REFINERY. VE Refinery. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://ve-refinery.ch/blogs/blog-ve-refinery-alcohol-free/how-do-you-remove-alcohol-from-wine

World Cancer Research Fund. (2018, - -). Alcoholic drinks and the risk of cancer. World Cancer Research Fund. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Alcoholic-Drinks.pdf

World Health Organization. (2022, May 9). Alcohol. World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol

World Health Organization. (2023, March 2). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. WHO Technical Report Series. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf?sequence=1

World Health Organization. (2023, April 15). A public health perspective on zero-and low-alcohol beverages. Snapshot series on alcohol control policies and practice, -(10), 22. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366740/9789240072152-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Appendices

Appendix 2 - Definition of no and low alcohol wine (NOLO)

This appendix defines the NOLO thresholds and scope used in the analysis.

Similar to “natural wine”, there is no standard definition for NOLO. A 0.7% ABV wine may be classified as “low alcohol” in the UK, but “non-alcoholic” in China, due to varying regulations (Anderson et al., 2021; Sam et al., 2021)

In this paper we will adopt the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) thresholds of <0.5% ABV for no alcohol wine (OIV, 2012).

We will adopt >=0.5% ABV for low alcohol wine, up to the typical ABV of that wine style (typically ~11% ABV at a minimum, though this varies by wine style) in cases where the alcohol reduction is >20% (OIV, 2012).

We will only include wine where alcohol has been reduced post-fermentation to be intentionally marketed as NOLO. Therefore, we are excluding wines such as sweet Riesling, Moscato d’Asti, or California wines with reduced alcohol for tax reasons (BevZero, 2023).

We are also excluding non alcoholic products that have never been through the fermentation process, such as grape juice or herbal infusions.

An interesting side note is that reducing alcohol for tax reasons was a primary driver of business for alcohol reduction service providers such as BevZero, who had to diversify their income stream after a change in US tax law on higher alcohol wines resulted in less demand for alcohol reduction services.

Appendix 3 - Best selling products on Boisson are priced higher than traditional wine

This appendix summarizes pricing context for best-selling NOLO products in the cited dataset.

(Boisson, 2023)

Figure: Boisson best-selling NOLO products and pricing.

Figure: Boisson best-selling NOLO products and pricing.

Comments